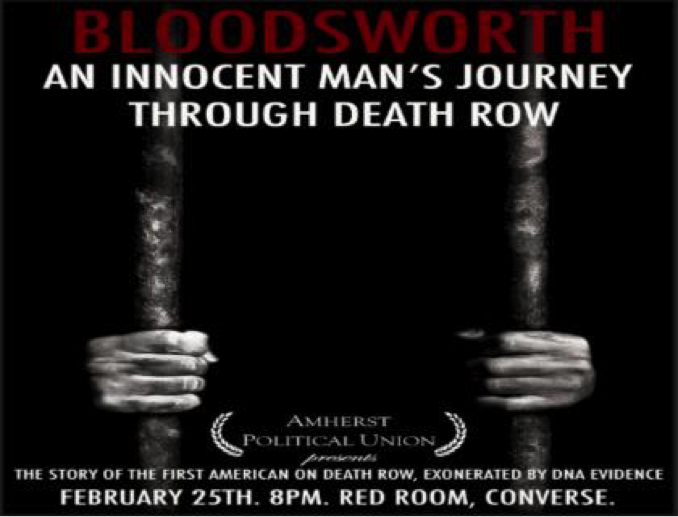

As students shuffled into Converse Hall’s Cole Assembly Room last Wednesday night, a gray-haired, casually dressed, beefy, not-quite-6-foot-man with a Van Dyke mustache lounged in the front row of the auditorium. The Amherst Political Union, who hosted the event, soon introduced the man as Kirk Noble Bloodsworth, the first American on death row to be exonerated by DNA evidence.

Bloodsworth took the podium, his presence commanding the audience’s attention and striking each student silent and still in their seats. As he opened his mouth to speak, the sound system misbehaved and erupted in an intense, theatrical score from an open YouTube tab.

The tension in the room abated and Bloodsworth playfully commented, “Just trying to keep things dramatic.”

That wasn’t going to be hard.

On a hot summer day in August 1984, Bloodsworth, then 22 years old and a former Marine, heard a hard knock on his front door. A squadron of police officers awaited him on the other side, welcoming him with a slew of words that explained his Miranda rights and placed him under arrest for the rape and murder of Dawn Hamilton, a 9-year old girl found dead and battered in the woods 15 days earlier.

“They said to me, ‘Kirk Bloodsworth, you’re under arrest for the first-degree murder of Dawn Hamilton, you son-of-a-bitch”, he said to the audience.

Although there was no physical evidence against him, and his conviction rested entirely upon eyewitness identification, Bloodsworth was eventually convicted in 1985 and sentenced to die in Maryland. Once inside the maximum-security confines of the Maryland Penitentiary, which looms like a foreboding, medieval castle in East Baltimore, Bloodsworth recognized he would probably never see the outside world again.

Yet for nearly nine years of conviction in the state’s most brutal prison, Bloodsworth relentlessly maintained his innocence while the media and public condemned him as a ruthless monster. In his lecture, he held the audience’s attention with a vivid description of penitentiary life. From stories of fellow inmates stabbing their eyes with pencils to the constant slew of licentious threats to beatings via chains and Master Locks, his account hammered home the horrors and brutalization of prison life. While on death row, Bloodsworth worked as the prison librarian, reading everything from “Gestalt psychology to Stephen King novels,” he said. One day, he came across a book about a man who was convicted of murder based on advanced DNA testing.

“I thought to myself, if you could be convicted by DNA testing, why couldn’t you be exonerated on the same grounds?” Bloodsworth said.

After that realization, Bloodsworth committed himself to establishing his innocence via this new technology. Finally, in the summer of 1993, Bloodsworth was declared a free man and a sleek limousine arrived outside the penitentiary to pilot him home. The Baltimore radio stations played songs in his tribute all weekend long. Cigars, beer, crab, and a three thousand dollar government stipend awaited him upon his return. Bloodsworth was a monster no more.

His formal exoneration did not occur until a decade later, when DNA evidence came to his aid once again and identified the actual killer in the Hamilton case, Kimberly Shay Ruffner. Only weeks after the Hamilton murder, Ruffner had been arrested for an unrelated incident that involved a burglary, rape and attempted murder. He had been doing his time one floor below Bloodsworth at the Maryland Penitentiary.

However, even after his release from prison and eventual exoneration, Bloodsworth could not shake the circumstances that led to his false conviction. He could not adjust back to a society with a justice system so flawed that innocent persons found themselves on death row.

“If it could happen to me, it could happen to anybody,” he said.

Now 56 years old, Bloodsworth has dedicated his life to eradicating the death penalty in America and establishing the Kirk Bloodsworth Post-Conviction DNA Testing Program, which will help finance the cost of post-conviction DNA testing. He works closely with The Innocence Project, a non-profit legal clinic revolving around post-conviction DNA testing, and ardent supported of the Innocence Protection Act, the first federal death penalty reform in be enacted in United States criminal law.

When asked by an audience member if he thought Ruffner, Dawn Hamilton’s actual killer, should face execution, Bloodsworth remained staunchly anti-death penalty. He reasoned, matter how many guilty men deserve to be on death row; capital punishment is not worth its inherent risks.

Bloodsworth shared the credo that drives his dedication of ending the death penalty: “You can free an innocent man from prison, but you can’t free him from the grave.”