There are good movies, bad movies and weird movies. And once in a while there comes a movie that defies what you think you know about cinema. With chills running down your spine, you stare at the screen for the entire run. And when the lights finally come on, you sit still, stunned, every part of your body palpitating.

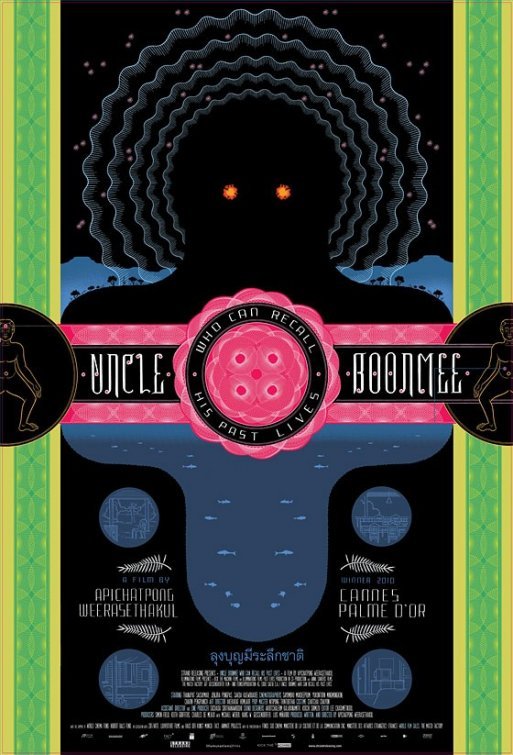

“Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives” (shortened below as “Uncle Boonmee”), the first Thai movie ever to receive the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, consists of vignettes of the eponymous character in his last days with acute kidney failure. I wish I were able to give a more detailed plot summary, but this is not a film that falls within norms. It is hardly a story, but rather a floating world of reality and mystique.

Yet, instead of collapsing in the absence of logical development, the mesmerizing images come to life with crystal-clear transparency so palpable that the film easily immerses its viewers candidacy and imagination. The film opens with the shot of an ox breaking away from the leash and prancing across the night jungle, pulled back by its owner. Without any background, explanation, conversation or mood-setting music, the camera remains focused on the creature in a typical portrait shot. From that moment on, the film glides with an atmosphere so quiet, yet lively and powerful, that it hinges on majesty. Though unusually static, each frame flows like full-bodied molasses. Truly marvelous is its capacity for invoking intense wonder and suspense while maintaining a slow, mellow pace.

Though it can be hard to imagine a film focused on the travails of life when so few main characters are human in the normal sense, “Uncle Boonmee” blends the natural and the supernatural into a captivating experimental narrative by challenging the boundaries between the two. The film carries mundane dialogues honestly saturated surrealism in scenes of Uncle Boonmee’s recalls. The mesmerizing sequence of his traveling in the cave that he believes to be his soul’s birthplace, stripped of all else but intimate sounds and psychedelic visuals, amplifies the lush sense of alternative realm while remaining intimate with reality. Everything looks foreign and familiar at the same time.

The film exemplifies the power of an exploratory perspective from an Asian culture heavily influenced by Buddhist traditions. Relying on the belief that everything is a life on its own, the film expresses the longing for life and memories through interspecies communication. This includes the entrancing dinner scene with Uncle Boonmee’s dead wife and his hirsute son returning as “Monkey Spirit” as well as a sex scene between an aging princess who sacrifices her material possessions to regain youth and the Lord of the Waters, a catfish.

These larger-than-life episodes, however absurd, contain Weerasethakul’s most acute introspective on loss, nostalgia, attachments and abandonment. In the final moment, we have Aunt Jen, who has been taking care of Uncle Boonmee, and a monk dressed in secular clothing about to go dining. As they leave the room, the monk turns around to see the two of them peacefully watching TV on the bed. On that wild note, Weerasethakul indicates that we live with the same serenity even in the face of absurdities. After all, it is life. But is it only that?