In its very first shot, Martin Scorsese’s “Hugo” sucks you into a magical, wonderful new world and refuses to let you go. The camera pans over the 1930’s Parisian skyline, but this is not the “real” Paris; it is the enchanted city of lights and love that Americans have been so fond of imagining for decades now (we saw it most recently in Woody Allen’s “Midnight in Paris”). Lingering only for a moment to allow the city’s supernatural allure to sink in, Scorsese soon descends into the train station at Montparnasse, floating down to the platform in one smooth, digitally-enhanced shot that must be astounding in 3-D (I saw the film in good old-fashioned 2-D, which I would still recommend if you like your films to be brightly lit and non-headache-inducing). The audience flies through steam, sound and bustling crowds, reminding us of the extraordinary tracking shot at the Copacabana in “Goodfellas,” until pulling into a tight close-up of a single, strikingly clear blue eye.

This is our titular hero, a young boy played by newcomer Asa Butterfield with astounding presence (those painfully bright eyes help a lot). Hugo Cabret literally lives inside the walls of the station, keeping up the building’s complex and rather massive array of clocks. He learned his craft from his kind father (Jude Law), who, in a twist straight out of a Roald Dahl novel, was killed in a mysterious fire. Aside from mechanical repair, Hugo seems to spend most of his day avoiding the searching gaze of the Station Inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen) — a bumbling but proud man who was wounded in World War I — or trying to fix a mysterious robotic automaton left to him by his father.

In order to get the parts he needs, Hugo surreptitiously steals from an elderly toy-maker (Ben Kingsley) who has set up shop in the station. Finally catching the resourceful orphan in the act, the crabby old man punishes Hugo by taking a journal from the boy that belonged to his father, containing the secrets to repairing the automaton. Desperate to get the journal back, Hugo enlists the help of the man’s goddaughter, Isabelle (Chloë Moretz), a voracious reader eager to emulate her literary idols and have an adventure of her own.

Isabelle bandies about titles like “Peter Pan,” “Treasure Island” and “The Wizard of Oz,” and for its first half, “Hugo” (based on the illustrated novel “The Invention of Hugo Cabret” by Brian Selznick) is a thrilling children’s tale worthy of any of those legendary fantasy escapades. The world of the Montparnasse station is beautifully crafted (in particular, the mechanical underbelly where Hugo dwells is an absolute marvel of set design) and populated with a host of vivid characters, many of whom are given only a fleeting few moments of screen time but nonetheless leave an impression: besides the menacing, dour Station Inspector, there is an imposing bookshop keeper (Christopher Lee), a charming flower girl (Emily Mortimer) and a delightfully adorable old couple (Richard Griffiths and Frances de la Tour).

The kids themselves are a winsome pair, with Hugo quiet but determined and Isabelle exuding an infectious sense of wonder. Together they rush through their encounters with an appropriately childlike enthusiasm that is perfectly entrancing. The film’s 127-minute running time flies by in such company, and viewers (or at least this viewer) should delight in returning to this fairy-tale place for many years to come.

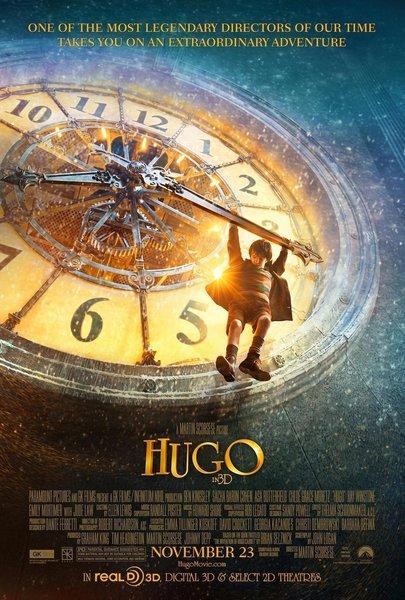

And that would probably be enough to recommend “Hugo” on its own, but somewhere along the line the movie transforms from a simple children’s adventure to nothing less than a glorious tribute to film itself, and to the pioneers of early, silent cinema in particular. An early scene of Hugo and Isabelle in a theater watching Harold Lloyd’s classic “Safety Last!” starts things off (Scorsese will later pay even more direct homage to Lloyd’s perilous clock-dangling scene), but the nostalgia really gets rolling with the revelation that Isabelle’s godfather Georges, the grumpy toy-store owner, is none other than cinema’s first magician, the incomparable Georges Méliès.

If that name doesn’t immediately conjure up images of fantastic under-sea worlds, trips to the moon, dancing skeletons and magical creatures, you’re probably not alone. Not many people (outside of France) are aware of the work of Méliès, a true revolutionary who employed almost every traditional special effect known to man (dissolves, multiple exposure, time-lapse photography) to trick his audiences. The story of “Hugo” becomes the story of Méliès, and as a film history nut who practically drools at the mention of hand-painted film reels, I was enraptured by this fascinating (and apparently completely true) tale. It’s possible that less cinephilic viewers will think this biographical section drags on a bit, but hopefully the remarkable journey of how one of the most famous filmmakers in the world became a forgotten toy-maker toiling away in a Parisian train station is enough to hold one’s attention.

The transition from fantasy to homage is a remarkably natural one, maintained by the constant sense of awe that pervades both parts. I don’t think there is any director working today who loves movies more than Martin Scorsese; growing up, the asthmatic New Yorker spent almost all of his time inside theaters, and his love of the silver screen led him to become not only a filmmaker himself, but also a dedicated film historian and preservationist. Scorsese is responsible for some of the greatest movies ever made, but none of them have felt so intensely personal as “Hugo.”

There are a thousand details to appreciate about “Hugo”: the unexpected depth of the at-first villainous Station Inspector, Kingsley’s exceptional performance, a heart-pounding train crash sequence, an abundance of visual references to everything from “The Great Train Robbery” to “Intolerance” and the films of Jean Renoir. And as always, you can expect impeccable work from Scorsese’s technical crew, including cinematographer Robert Richardson and editor Thelma Schoonmaker. The distinct lack of blood and violence may turn off fans of Scorsese’s mobster classics, but “Hugo” is a cinematic spectacle worthy of consideration among the master’s best.