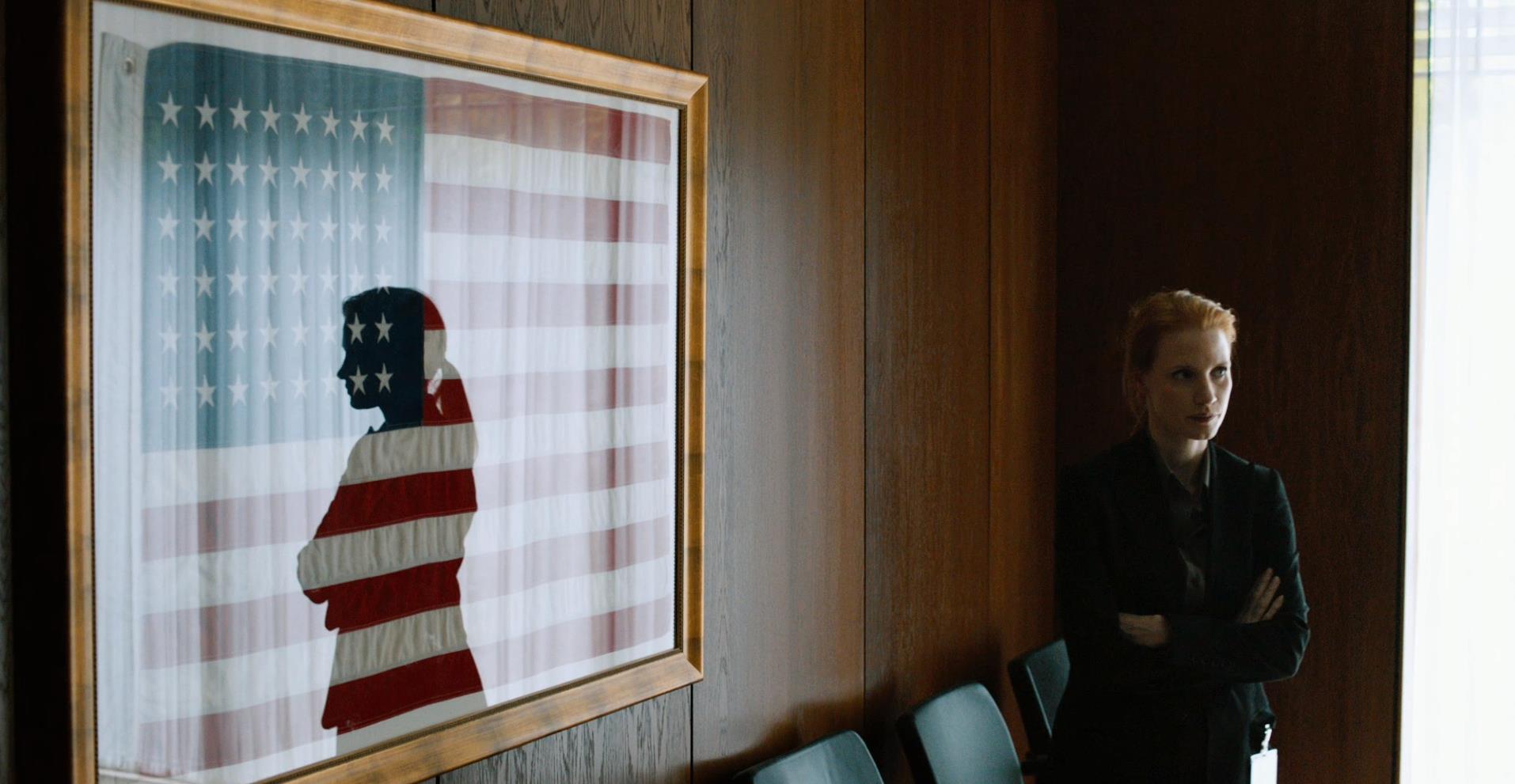

In the past few months, much has been written about “Zero Dark Thirty,” Kathryn Bigelow’s dramatization of the hunt for Osama bin Laden through the eyes of fictional CIA officer Maya (Jessica Chastain). By a wide margin, it’s the best-reviewed film in what was generally a pretty good year for films. It’s been praised as a more than worthy follow-up to director Bigelow’s and screenwriter Mark Boal’s Oscar-winning previous release, “The Hurt Locker,” and was at one point all but assured to win throughout the year’s round of awards. “Zero Dark Thirty” deftly raises questions about the morality of torture and its use in the War on Terror, leading many to consider it the preeminent docu-drama on America’s role in the global sphere. Whatever your opinion about that may be, the film deals with weighty material, and more than one person has claimed that “Zero Dark Thirty” will stand the test of history as a companion piece to the numerous books, documentaries and journal articles written about America’s involvement in the Middle East.

However, the film has also been the victim of some unfortunately simplistic but pressing complaints about its treatment of torture. Perhaps due to these complaints, it’s rapidly fallen off the Academy’s list of favorites. Kathryn Bigelow was robbed of a deserving Best Director nod — the last film to win Best Picture without a director nomination was released in 1989. That, added to the fact that “Zero Dark Thirty” hasn’t gone on to win any other major award so far this year, all but spells defeat for the movie. “Zero Dark Thirty” is a controversial film, and that’s likely exactly what it wants to be; while the largest outcry against the film is simplistic and poorly informed, this film more than any other this year is one that merits careful attention and debate. People should feel uncomfortable about “Zero Dark Thirty” precisely because the material it depicts is uncomfortable. However, that doesn’t make it a bad film; it is exactly why the film is both important and memorable.

The discussion surrounding “Zero Dark Thirty” is unfortunate not because the film’s depiction of torture isn’t worth discussing, but because it grossly oversimplifies the issue in a way the film does not. The film does depict several instances of grisly torture inflicted by the U.S. government on an individual believed to hold ties to Osama bin Laden, which many assume implies an endorsement of U.S. actions. It seems to me that the individuals in question aren’t comfortable admitting that U.S. operatives likely did engage in torture and that this may very well have led to useful information in the hunt for bin Laden. They don’t want to believe that torture can procure useful evidence or that the U.S. would engage in such actions. This isn’t to say that torture is necessarily the most efficient means of procuring information — however, it very well could have led to information, something the film depicts starkly, brutally and perhaps all too honestly. The question, to these people, seems simply to be whether torture can lead to useful information, and not the more pertinent and difficult question that the film raises but which few viewers are debating: whether that information, even if useful, is worth procuring and using if it means having to engage in torture in the first place. It’s almost heresy to directly state that killing Osama bin Laden wasn’t a total and complete good for the world, but this really is an important question that needs to be asked. If killing a mass murderer requires engaging in morally questionable acts, are the ends worth the means? It is a difficult question with no easy answers, and one which the film does not avoid.

I have devoted much time to the complaints raised against the film — not out of respect for those complaints, but out of respect for the film’s capacity to raise discussion. Had it been any other film, I likely wouldn’t have cared. However, “Zero Dark Thirty” is a film of uncommon intelligence that serves above all else to raise questions and leave the viewers to decide the answer for themselves. It is ruthlessly complex, yet shockingly straightforward; stark, yet full of life; immediate, yet distant; elusive, yet obvious; and unnerving, yet all too comfortable in an age of desensitized violence in fictional media and 24-hour media coverage of real-world events. This mass of contradictions doesn’t really do justice to a film as deceptive as Bigelow’s portrait of war and the men and women who fight them, and no one word or person really could do justice to it. That is the point, without which the film would lose its mystery. It is a film that exists to promote discussion, not to make a statement. Bigelow knows this too, letting the material speak for itself and purposefully hyper-realizing it by straying away from cinematic tricks and flashy cinematography. Above all, this is what lends the film an almost documentary-like feel, and it is what makes the film both enrapturing and difficult to sit through.

Even when Bigelow resorts to bolder techniques, she always presents them in a manner that is contradictory to our expectations. Take, for example, the film’s treatment of the climactic events of the night of May 2, 2011, when a group of US soldiers stormed a compound they believed could hold their target and shot a person whom they believed to be Osama bin Laden. The scene is shockingly subdued and silent when most filmmakers would present it with all the bombast they could muster. Bigelow never gives us any one character to truly connect to or follow and keeps us at an arm’s length. Simultaneously, she paints the scene in the green light of night vision, the vision of the soldiers themselves, and frequently cuts to first person viewpoints of the mostly nameless soldiers, thereby giving us the personal view of a stranger who doesn’t understand exactly what he’s going to find. Of course, we do, and that’s what makes it all the more unnerving. The scene takes its time but unfolds with almost ruthless efficiency, and Bigelow’s ability to throw us into the mix through first person shots while still keeping us at arm’s length gives the film a unique and uncompromising feel. I would say fascinating, but that sounds almost too intellectual and doesn’t quite capture the immediate punch to the gut that the film gives us despite its quiet, somber nature. It captures that feeling of, “So what now?” all too well, recalling the 10 years which millions of people spent wondering, actively or passively, what happened to the man who bombed the World Trade Center, as well as the mixed emotions of realizing there was no more looking and coming to terms with whether anything had truly been accomplished over those ten years.

No scene epitomizes this feeling more than the final shot of Maya waiting on a plane after the raid and being asked, “Where do you want to go now?” In one of the finest reaction shots ever committed to celluloid she gives us too many emotions to list, encapsulating 10 years of searching now gone and no foreseeable future and leaving us wondering that exact under- yet overwhelming feeling of, “So what now?” For all its grand ambitions, “Zero Dark Thirty” is Maya’s story as much as it is the story of the hunt for Bin Laden, and in the final scene we realize that, to her, there is little difference between these two. “Zero Dark Thirty” harrowingly raises many questions about the effectiveness and ethical nature of the distinctive U.S. brand of counter-terrorism. Above all, however, the question it most profoundly leaves us with is what it is like to spend ten years of your life with only one goal when that goal is to find and kill a man, regardless of his past actions. Is “Zero Dark Thirty,” as many have claimed, fascist? Is it the best film of the year? Or is both? Perhaps that’s not for me to say. The simple answer, though, and the most important one, is that you should watch it and decide for yourself.