When I say “queer graphic novels,” what comes to mind? My guess would be not much; it’s not a combination of words that generally appears together. Alison Bechdel, however, has managed to make a fine career out of this combination. Her most famous work, Fun Home, was named the Best Book of the Year in 2006 by Time magazine and her career has spanned 25 years with no sign of stopping soon.

So, why should you care about her work? Maybe you think that all comics are like Superman, or you just aren’t interested in queer stories. But I’d argue that her works are much more than just graphic novels about queer characters. If they were, they’d have remained popular only in that niche; her books wouldn’t be taught in college classes across the nation (including here at Amherst) and she wouldn’t have been one of the headliners at Smith College’s recent celebration of its archives, an honor also accorded to Gloria Steinem. Instead, her work challenges us as readers, both intellectually and by providing a glimpse into a world that’s difficult to imagine.

Her first comic, “Dykes to Watch Out For” (DTWOF), has the unusual distinction of being both her longest and her least-known work. Launched in 1987, this strip ran in gay and lesbian newspapers throughout the country until 2008, when she put it on hold to work on second graphic novel, “Are You My Mother?” (Don’t hold out hope that she’ll pick it back up; at her talk at Smith, Bechdel said it was unlikely.) The entire series has been published in a number of strip collections and in 2008, “The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For” was released, containing the most important plot lines of the comic’s 21-year run. It’s a comprehensive tome, and I recommend it to any unfamiliar readers who want to take a look at Bechdel’s primary work.

Originally a series of one-off comics, a recurring cast appeared early in the series’ run and quickly became its cornerstone. The early comics can be rough: her art seems messy and frazzled, and she clearly hasn’t quite gotten the characters nailed down yet. While at times it feels repetitive, the characters become grounded and quite likable. Furthermore, it’s also a fascinating read from a historical perspective, as Bechdel was heavily influenced by then-current events, whether it was the historic marches on Washington in the early 90s, or liberal angst about George W. Bush. Many of the backgrounds throughout the comic are based on real things Bechdel saw during this time period, which adds to this historical atmosphere. It’s a look into a world that’s hard for us to imagine today — sure, you can read about these events, but how often are you able to actually get a sense of what it was like to be there? It allows us to connect to this history in a way that neither stories nor pictures alone could really do. The strip is a fascinating perspective on the sights, sounds and emotions of queer life in the United States that is hard to find elsewhere.

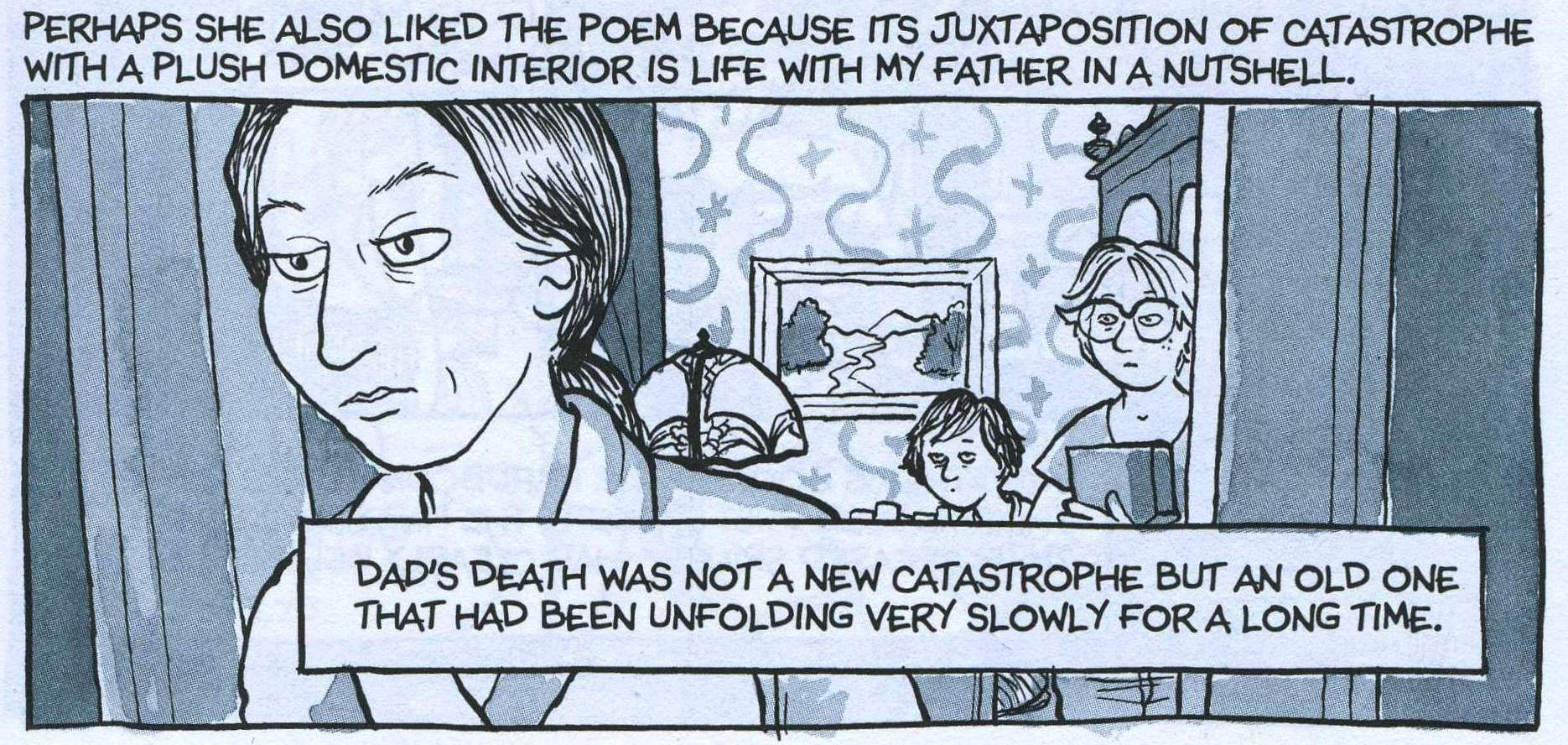

In 2006, almost 20 years after she began her career, Bechdel burst into the mainstream with her most famous work, “Fun Home.” In a drastic step away from the newspaper comic strips of DWTOF, Bechdel tells the story of her father, a tyrannical, deeply closeted individual who, Bechdel believes, killed himself when she was 19. She manages to avoid the melodrama that the subject matter might command, thanks to her analytic writing and honesty that makes it much more about discussing her relationship with her father than dwelling on him. The book itself is very intelligently written; it’s told out of order, with some events discussed multiple times from different perspectives, but it always manages to feel fresh and natural. She masterfully uses literary and mythological references, at one point comparing her father to Icarus and then later to Marcel Proust. It allows us to view her subjects from another angle, and it works. Her art style compliments this story; each frame was carefully researched and planned by Bechdel, using old family photos to get each room precisely right and photographing herself in the character’s poses to get the right perspective. The panels are all shades of a dull green wash, which adds to the atmosphere Bechdel evokes in the book. Despite the elaborate story and the intricate panels, it all comes together spectacularly. Like DWTOF, “Fun Home” also gives us a glimpse into recent history. She shows us everything from what it was like to be coming out in the 80s, to a child’s perspective on Watergate, and the success of the story is due to how immersed we get in her world.

After “Fun Home” analyzed her relationship with her father, her next (and most recent) book, “Are You My Mother?”, delves into her even more complicated relationship with her mother. Her mother was easily one of the more complex characters in “Fun Home,” so seeing this relationship expanded upon here is a natural follow up. While it may sound like this is just a retread of her most-known work, “Are You My Mother?”, if anything, pushes Bechdel’s writing beyond what it was in “Fun Home.” While her relationship with her father had a clear story to it, her relationship with her mother is much less clear-cut, and as she points out, still ongoing. Released six years after “Fun Home,” Bechdel’s writing has clearly advanced since then. She still uses the anachronistic framing and the literary allusions, but at a deeper level than before. Much of her analysis of her relationship with her mother is interwoven with the work of 20th century psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, as well as Virginia Woolf’s “To The Lighthouse.” While delving deeper into these comparisons, she gives the book an interesting framework, though it can be hard to follow without a background in the works she’s discussing. It can also be harder to relate to this than “Fun Home,” particularly for our generation, as the story is more focused on an older Bechdel. Despite this and its looser focus, it comes together nicely in the end.

At this point, Bechdel has published hundreds of comic strips and two full-length books. While these books, her current focus, take an enormous amount of time and effort (seven years for “Fun Home” and a similar amount for “Are You My Mother?”), her results are thoroughly fascinating and above all, unique in both the worlds of queer fiction and graphic novels. We get an immersive look into the recent past, one that might be hard for us to imagine otherwise. Both her writing and her art add layers to the stories she tells, but it never manages to feel overly complex. For anyone looking for an intricately written work that steers clear of the genre conventions, I highly recommend Bechdel’s work.