Following his suspension from Jones College Prep High School in 2011 for marijuana possession, high schooler Chancelor Bennett put out his first mixtape, “10 Day,” and began to take his aspirations of becoming a musician seriously. In 2013, he broke through the music scene with “Acid Rap,” and since then has been working on collaborations with multiple artists, never quite settling down to work on a solo project. When he announced that his new mixtape would be dropping in the month of April, I honestly told people that the news cured my depression. In a world of dropping black bodies and dropping bombs, I’m rarely, if ever, not depressed. But Chance’s music reminds me that, among other things, there’s hope.

The music video for one of the new mixtape’s tracks, “Angels,” features a young boy, Chance’s usual trippy self, and Saba. The song is an opportunity for the rapper to celebrate his personal growth over the years, rapping as he flies through the Chicago skies, “I’m the blueprint to a real man,” and declaring that he wishes to “clean up the streets so [his] daughter can have somewhere to play.” Meanwhile, on April 1, CNN reported that residents fear a “long, hot summer” in Chicago after a massive spike in gun violence since the start of the year. According to NPR, the spike in violent crime seen in Chicago this year coincides with increased scrutiny on police misconduct. Cops, afraid of being the subject of “the next viral video,” have thus become more passive in pursuing criminals. Nonetheless, the systemic problems at play would not be cured by increased police activity and aggression. Treating angels like criminals will not save them, and Chance knows this.

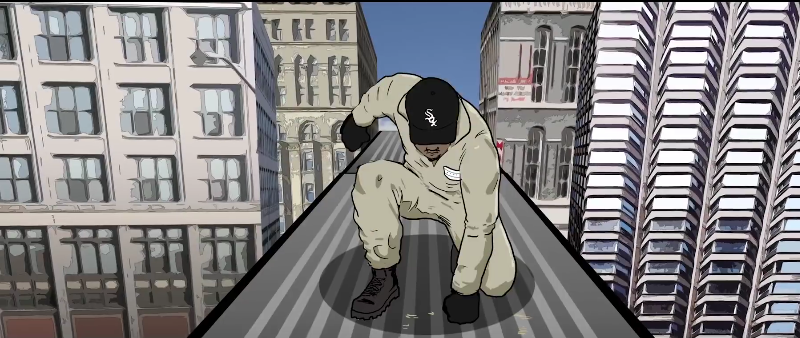

In “Paranoia,” technically the latter half of the track “Pusha Man” on Acid Rap, he raps about the gang violence that plagues Chicago and other American cities, alongside fear of refugees, police brutality and the paranoia of pushing drugs as a black man. In releasing “Angels,” Chance has assured us that his upcoming mixtape will be just as real and authentic as his previous works. He’s stuck to his unique sound, and most importantly, he’s stuck to the issues he cares about most. With rich rhythmic textures, upbeat singing and rapping, dope beats and a simple melodic chorus by Saba, the song itself embraces nothing but positive vibes. The video consists of a flying cartoonish Chance, Chicago subway riders dancing and a concluding duo dance with Chance the Rapper and Saba in the middle of a street. The final shot zeroes in on the young boy with whom the video originally opened, a cartoon halo hovering above his hooded head.

Chance the Rapper’s art is integral to the creation of new narratives about black people, and especially black men. This didn’t keep New York Post writer Phil Mushnick from calling Chance’s music “standard dehumanizing gangsta rap” when criticizing the decision of the Chicago White Socks to form a paid partnership with him. When describing the complex situation of gun violence in Chicago, Mushnick offered a gross oversimplification, saying, “Chicago is known as our murder capital. Gun-toting, itchy-fingered gang members, as young as 14, daily and nightly murdering and being murdered — children shooting children dead — over nothing more than a sideways glance, the wrong-color shirt, a bag of weed and, now in its 27th year, status-symbol sneakers.” Of course, Mushnick would likely respond with silence if asked about the history of Chicago’s housing project communities.

Those like Mushnick listen to Chance without actually listening to Chance — and this can result in blatant racism, as exemplified above, or something more insidious, like white boys bobbing their head to his beats and claiming to be fans without taking the time to consider Chance’s deeper messages. Like many black artists, he is continually depoliticized and divorced from the issues with which his art is concerned. This truism became particularly manifest for me this past Wednesday, when Snapchat commemorated 4/20 with a Bob Marley filter that reduced a man’s legacy from radical political activism to something more digestible for white society — smoking weed. Marley’s most popular hits — “One Love,” “Three Little Birds” and others — are used to keep his true musical legacy in the shadows. Similarly, songs like “Smoke Again” by Chance The Rapper are used by Mushnick and others to discredit his work, or to tune him out when his words become more political.

In spite of this, Chance’s head stays high, and his music remains touching and powerful. When his next mixtape drops, the ground will shake. Our job is to listen.