Peter Millard ’76 was once a chemistry and German double major at Amherst, unsure of whether or not medicine was the right path for him. After graduation, he discovered his true passion for helping the poor by using the tools of medicine and public health. Millard’s interests and penchant for adventure have led him to serve patients from Bolivia to Zimbabwe and become the director of a community health center in Maine. His dedication to tackling public health problems has resulted in an invention that could transform the fight against HIV and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa.

Serving the Underserved

Millard grew up in rural Maine near the city of Portland. After high school, he attended Amherst because of the beauty of the campus and its surroundings, the college’s small size and its proximity to home. He majored in chemistry because he liked tackling challenges. He also majored in German, which allowed him to study abroad in Germany for a semester.

“I think I did it because I wanted to get away from science a little bit and do something different,” Millard said of the German major. To him, focusing solely on science was both stressful and boring, and learning German provided the perfect balance.

Like many Amherst students, Millard had an interest in medicine but was not entirely sure that he wanted to pursue a career in the medical field. Following graduation, instead of diving into medical school, he took a year off to hitchhike from Maine down to Bolivia, where he volunteered at a hospital that primarily served a poor indigenous population in Cochabamba.

“Once I started doing that, then I realized that I wanted to dedicate myself to serving the poorest people, the underserved,” he said.

With more certainty about the path he wanted to follow, Millard returned to the U.S. to attend medical school at the University of Vermont.

Treating Individuals, Benefiting Communities

Millard was drawn to the practice of family medicine because it would provide him with a wide variety of skills that he could use in working with underserved communities and populations. While he could see how specialties such as cardiology could be intellectually stimulating, the real appeal of being a medical doctor was in being able to care for the patient as a whole person.

“It’s what surrounds the heart that’s important, I think — the personality and the problems that people have,” he said. “It’s really interesting to hear people’s stories, and if you’re a doctor, you spend a lot of time listening. And you have to listen to some very sad stories about people’s lives, because people’s lives aren’t always easy.”

After finishing his medical training, Millard worked at a rural hospital in Zimbabwe. His wife, Emily, also worked at the hospital as a nurse, and they brought their three children with them. It was the 1980s, and the country had just won its independence from British control at the beginning of the decade. Millard found Zimbabwe to be interesting and relatively safe. However, its neighbor Mozambique was caught in a long and deadly civil war, and Millard worked near the Mozambican border.

“We saw a lot of casualties — a lot of gunshot wounds, a lot of victims of landmines who came to our hospital and a lot of refugees who just had absolutely nothing,” Millard recalled. He and his wife often worried about the possibility that their family might also experience violence, so when their three-year contract came to an end, they made the difficult choice not to extend it and returned home.

During his time in Zimbabwe, Millard also developed an interest in public health. While physicians treat individuals, public health workers treat the community as a whole by targeting the root causes of sickness and preventing further spread of disease. As a physician in a region with widespread diseases and health problems, he wanted to find solutions that would extend beyond benefiting one patient at a time. Millard considers the greatest societal improvements in health — including clean water, increased public safety and protection against malaria and HIV — to be public health achievements rather than medical accomplishments.

After returning to the U.S., Millard got a Ph.D. in epidemiology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He conducted research and taught epidemiology at the University of Vermont and academic medicine at the Eastern Maine Medical Center’s residency program. Now, he teaches epidemiology at the University of New England. He has balanced patient care with classroom and clinical instruction, keeping “one foot in the clinical medicine realm and one foot in public health.”

Public health greatly broadened the scope of work that Millard was able to do to serve others. His training in public health and epidemiology allowed him to conduct research that would lead to groundbreaking work in combating the HIV and AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa.

Finding A Better Way

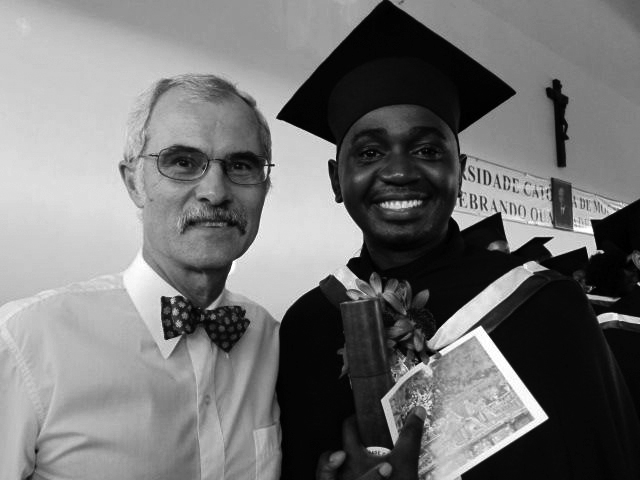

In 2008, Millard returned to Africa, this time to Mozambique. He taught at a medical school, where he began doing research on the HIV and AIDS epidemic and learned of the role of male circumcision in preventing transmission. Millard had once been opposed to routine circumcision and refused to perform it on newborns during his medical training, but he changed his mind after relatively new research demonstrated that circumcision decreased female-to-male viral transmission. The World Health Organization also recognized the benefits of male circumcision and aimed to circumcise 20 million men in the 14 countries with the highest HIV prevalence.

Seeing that circumcision could decrease the spread of HIV, Millard taught the procedure to his medical students. However, circumcising older boys and adult men is much more time-consuming and messy than circumcising newborns and required more skilled personnel.

With his research and public health background, Millard was able to design a new approach to adult male circumcisions. His method required less time and skill, was less invasive and used only topical anesthetic cream instead of an injected anesthetic. It relied on a specialized instrument, the Unicirc, which Millard invented and made disposable in order to prevent disease transmission from improperly sterilized reusable instruments.

Since developing the Unicirc, Millard has been collaborating with colleagues in South Africa to gather evidence that it is more effective than other existing methods. He has conducted clinical trials on adult men and adolescent boys which show that circumcisions using the Unicirc are faster and cause less adverse effects. The next step for Millard and his partners is to gain approval from the World Health Organization to use the device on larger groups of men.

Though Millard’s publications about the the Unicirc are all fairly recent, he has been fighting for years to fund the instrument and necessary clinical experiments. Since he does not come from a larger or more prestigious research institution in the U.S., it has been difficult to catch the eye of funding sources.

But without his background in research and epidemiology, Millard may never have been able to carry out his idea to revolutionize adult male circumcision.

“I was able to do the research myself to prove that it worked,” he said. “If you were a regular doctor and you got this idea, you wouldn’t have a clue how to go about proving that it was a good idea. But because I had the training in public health, it was easy for me to conduct and design a study and then publish it.”

Valuing Lived Experiences

After returning to the U.S. from Mozambique, Millard began his work at Seaport Community Health Center in Maine, where he does what attracted him to medical practice in the first place: treating patients who are primarily poor and in greatest need. He now directs that center, which provides family medicine care as well as programs such as drug treatment for addicts.

In community health, Millard faces many challenging situations and sees patients who come to him not only with health concerns but also with burdens in their lives, such as sexual assault, drug dependency or mental health problems. To Millard, being allowed into others’ stories is a privilege, and he considers it his duty to be sympathetic and provide help however possible.

In public health, Millard’s motivation for his work is the potential to create a better future — not just for the current generation but also for many generations to come.

Back in medical school at the University of Vermont, Millard met Richard Aronson ’69, current health professions advisor and assistant dean of students. Aronson called Millard a “lifelong friend” who shares “the ideals of service, critical thought, social justice, a fierce quest for a better world and humaneness that define Amherst at its best.”

“[Millard] exemplifies the highest ideals of medicine and public health,” Aronson said. “[He is] a brilliant thinker who cares deeply about his patients, with a passionate appreciation of the multiple dimensions of healing and a deep understanding, translated into action, of the social, cultural and psychological factors that are such major determinants of health and well-being.”

As an undergraduate, Millard never expected to become the person he is now, but he has found purpose in his career by following his passion and encourages current students to do the same.

To those who want to pursue careers in serving those in need, Millard suggests that they begin by living among those they want to serve.

“There’s plenty of need in the United States — you don’t need to go to South America or Africa,” he said. “Go and live in an underserved community and find out what it’s like. Find out what people are thinking and what problems they struggle with every day.”