The kind of films shown in smaller local movie theaters such as Amherst Cinema possess a unique and identifiable mood to them. True, there is remarkable diversity in both content and origin not found in the box offices, but such an abundance of life is communicated in an equally rarified manner. The films almost always nibble at life, reluctant to chow down upon any grand sweeping statements about society or the universe. In the worst cases, it is an absence of ambition garbed as aesthetic, a feature-length production in pursuit of the veneer of profundity while repulsed by the dirt of such depths. For all its flaws, “The Lost City of Z” does not fall prey to such proclivities and presents itself as an undeniably entertaining and occasionally moving counterpoint to the norms of its ilk.

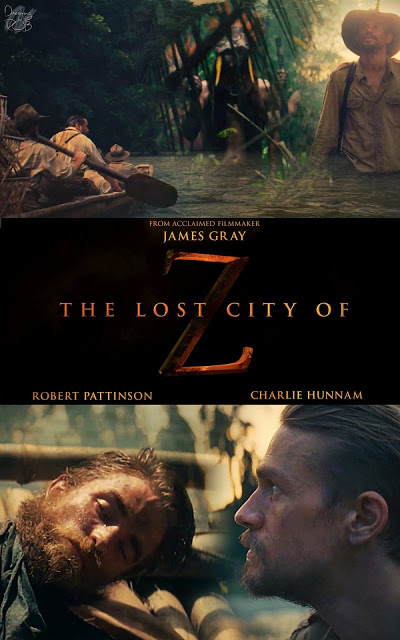

The differences represented in “The Lost City of Z” go against the grain of most small cinematic releases. It is a tale of mystery and discovery that shuns the fads of the modern adventure and deliberately throws itself headlong into the past. Specifically, “The Lost City of Z” finds itself in the fervor of imperial Europe’s charting and mapping of the so-called “New World,” with a contemporary perspective that sympathizes with the darkness on the adjacent side of the “Sun That Never Set.” Lieutenant Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett is the hero of this revisionist expedition, but first he is the son of a disgraced aristocrat. The promise of starting anew grips him as it did so many of his historical peers, and his unwavering belief in the existence of the titular lost city of Z amid the Amazon rainforests seems more than a little tinged by his personal and economic desperation.

A more conventionally conscious film would have focused on the duality of Fawcett’s character, exploring how his pressing need to escape the stifling orthodoxies of home inevitably and ironically hemorrhage into the destruction of equally complex and nuanced human beings abroad. And that movie, with the kind of eye for beauty and detail demonstrated by this film, would have been well worth the price of admission. The set-up, as it turns out, is even richer in its complexity. For one, Fawcett is convinced of the humanity of the indigenous people he finds in the Amazon. If the filmmaker was attempting to uncover the colonialist implications of his personal desire, then the end result was remarkably sloppy.

More importantly, the film deprives Fawcett’s quest to the Amazon of any lasting, redemptive dignity. That is to say, there is nothing honorable or morally grave about the lieutenant colonel’s quest, largely because he keeps coming back, and his constant return is the true center of drama. “The Lost City of Z,” in a sense, is a massive red herring, the exotic fetishism of the imperialist era only feeding into its misdirecting mystique. The real lost city is Fawcett’s own home, as he becomes alien to his own family and upbringing and more and more entranced by the initially shocking fulfillment of his dreams. It is more akin to “Heart of Darkness” or “Apocalypse Now,” with less blood and napalm, in that it tracks the transformation of the white everyman in the mysterious lands across the big lake.

The ravished obsession with which the camera shoots the Amazon rainforest emphasizes the dangerous beauty of the land that overwhelms the lieutenant colonel. Even in the loudest moments of spectacle, the green that hangs back never fails to engage the idlest eye and remind the viewer of the relentless, unfamiliar world. That charisma of the Amazon, however, is the one quality that does not quite rub onto Fawcett. He is more than competently acted, and the script is tight enough to endow his role with sufficient interest as to not hinder the unfolding of the long and expansive story. But simultaneously, there is a real sense that the background is overwhelming the foreground, and as much as that fact is a compliment on the former, it is also a partial indictment of the latter.

Yet as much as one can rag on the minute-pacing issues, the bloated episodes in between, and the sense that the film relies too heavily on the power of its premise, “The Lost City of Z” accomplishes a deeply original synthesis among the contemporary indie sensibility, the classic adventure tale and gravitas of the “true story” period drama. More than the mere sum of its derivative parts, it shines as a symbol of the familiar creativity of remix culture and rings a message of pulpy achievement in a time and arena of emotionally remote independent ventures. Watching this movie is its own kind of discovery, and the movie-going world is better for it.