Last week, Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas submitted a petition for statehood to the United Nations. Clearly a two-state solution is imperative to ending the conflict. Both sides realize this — according to a March 2010 poll, 72 percent of Israelis and 57 percent of Palestinians want a two-state solution. It’s the only hope of ensuring a lasting peace, delivering justice to the Palestinians and it’s necessary for the survival of Israel as a Jewish state. But although the petition has understandably raised the hopes and emotions of millions of Palestinians, it will not bring peace.

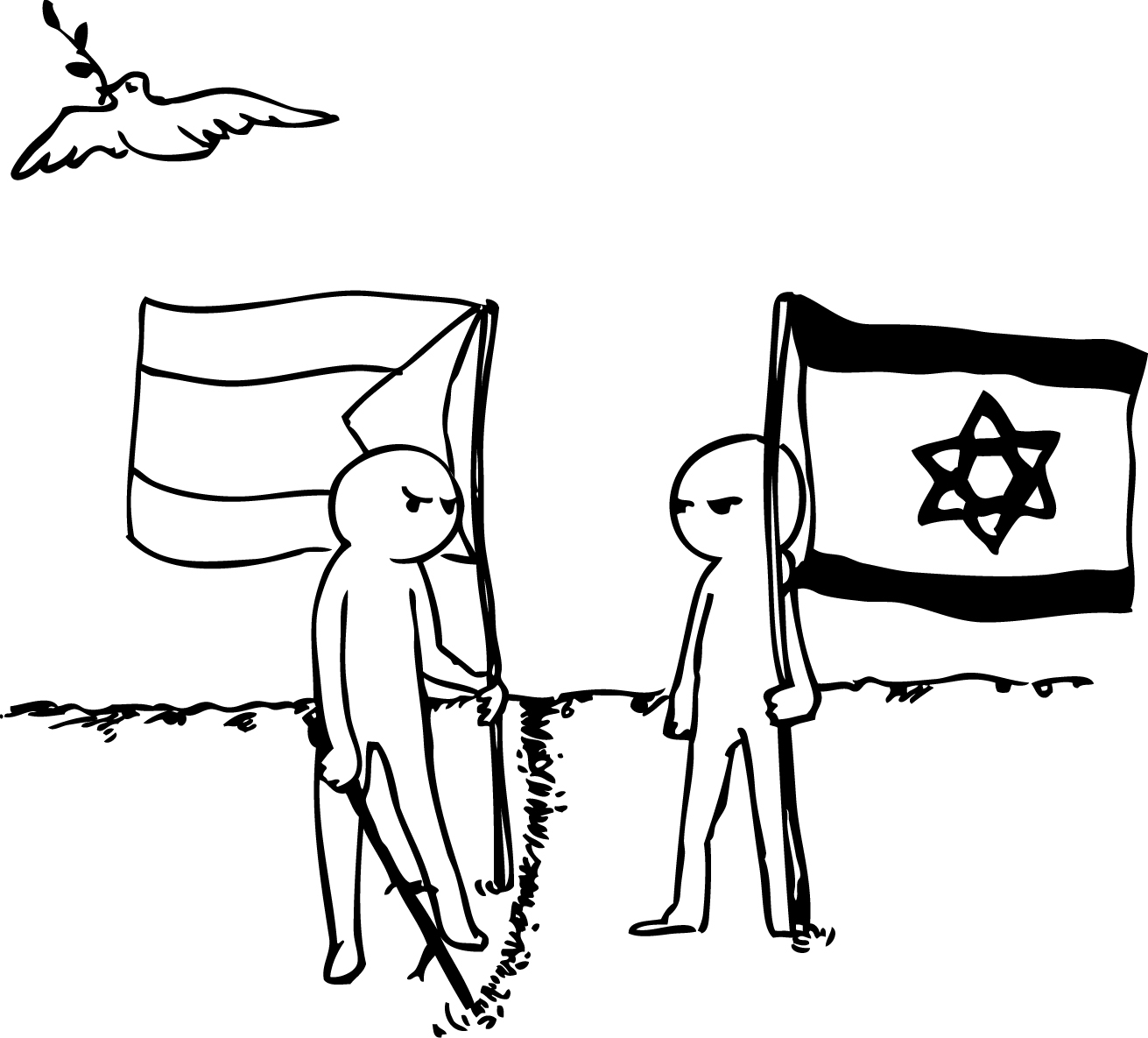

It’s easy to sympathize with the Palestinian situation, and their undeniable suffering. The settlement policy has been illegal and unjust as it divides farmers from their lands and prohibits free movement. It is less easy for Palestinian supporters to do the same with the Israeli situation, either because of the deep sense of being wronged, or Israel’s position of power over the Palestinians. But there will be no peace agreement without trust, and there can be no trust without empathy.

The Jewish people have been persecuted for centuries, having borne the weight of pogroms, expulsions, discrimination and genocide. The tiny state of Israel is surrounded by hostile neighbors and anti-Semitic leaders who call for it to be wiped off the map, by terror groups that have committed themselves to achieving this goal and by nations that have waged multiple wars against it.

The hard truth is that the core of the conflict is the Arab nations’ unwillingness to accept the existence of a Jewish state in the Middle East, even though Jews have had a continuous presence in modern-day Israel for thousands of years, from the Exodus to the Ottoman Empire. This has been the case since 1947, when they rejected a U.N. resolution that established two states of roughly equal size and placed Jerusalem under U.N. administration, and instead declared war on the day of Israel’s proclaimed independence. Across the Middle East, Jews, too, were made refugees. Shortly after Israel’s founding, nearly one million Jewish people were expelled from Algeria, Egypt and Iraq, or fled violence, pogroms and persecution in other Middle Eastern states.

Put in scale by population, the number of Israelis killed and wounded by terror attacks during the Second Intifada would be equivalent to 45,000 Americans killed. In response to the tragedy of 9/11, our nation embarked on two massive wars halfway around the world — both of which I was and am against, but the first of which friends of mine, who are pro-Palestinian, have defended to me. And so while Israel bears responsibility for the civilian deaths that occurred in its responses, do its choices to have a military presence in the West Bank, and build a security fence — a fence that has been remarkably successful in reducing the number of attacks and bombings — strike us as so incredible? What would our response have been the equivalent of 15 9/11s?

Throughout these decades, amidst security fears and violence that few of us have had to experience, Israel has remarkably remained the most open, democratic, and free society in the Middle East. Its Arab minority faces forms of discrimination that should not be overlooked, but they too recognize Israel’s successes and their own benefit in this regard. A representative survey of East Jerusalem found that a majority of Palestinians there would rather become citizens of Israel than a new Palestinian state, and 40 percent said they would move in order to live under Israeli, and not Palestinian, rule. Three-quarters are concerned that they would lose their ability to write and speak freely were they to live under a Palestinian state.

Israel has become increasingly isolated internationally of late, with the loss of two of its most important regional allies. In Egypt, the direction of the Arab Spring has been called into question as the regime seems to have slipped back into the old ways, using Israel as a scapegoat to deflect public anger. Turkey’s Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has used the flotilla incident to ratchet up the rhetoric against his nation’s former ally in a bid for a more prominent regional role. Nevermind that his administration still refuses to acknowledge the Armenian genocide (when roughly one million Armenians were slaughtered in the Ottoman Empire after WWI), is still occupying half of Cyprus (where a settlement policy has brought nearly 150,000 settlers to that portion of the island over the last three decades) and regularly engages in military strikes against the separatist Kurds.

Against this backdrop, the Palestinian U.N. bid for statehood threatens to further isolate Israel — and the United States — in the international community and the Middle East. None of this makes peace more likely. Peace will come as a result of negotiations between the two sides. A Palestinian state is a necessity, but will only guarantee peace if it arises as the result of negotiated peace. A state before peace will not deliver peace, but merely another Gaza situation — something Israel has no desire in repeating.

It is already known that the resolution will not pass the American veto in the Security Council, but Europe needs to vote against it as well — not out of spite to Palestinian hopes, but for them. The Obama Administration is willing to be a true friend and push Israel as hard as Clinton did at Camp David to make significant concessions for peace. This will only be more difficult if Israel feels isolated, and the point of reference becomes a U.N. resolution that has already determined a Palestinian state with 1967 borders.

Peace is difficult, and it will not be achieved through inflammatory speeches that neglect history, through intransigence that ignores suffering or through easy U.N. resolutions. Rather, both Netanyahu and Abbas need to stop demanding preconditions that should be the result of talks — borders, and recognition — and meet at the table ready to make a serious effort.