“From those to whom much is given, much will be expected.”

For Roger Creel, those words — one of the many mottos of his high school — did not take on the tone of obligation that might seem to pervade them. Rather, he held onto this quotation dearly, as a reminder that he has been invited to partake in the world wholly and without reservation. And the way Creel has responded to that invitation leads Professor David Sofield, his English adviser, to say that Creel is “the best example, in my 48 years of teaching, of somebody who was a true liberal arts student.” With the end of his Amherst career approaching and a double major completed in English and Geology, the latter department having awarded him summa cum laude and the prize for best thesis of the year, it would be hard for anyone to speak to the contrary.

Early Creativity

From the very beginning, Creel immersed himself in what he termed a “swirling mélange” of activities. At age five, he began his studies in piano; at nine, he traded in his hockey stick for ballet shoes. Throughout high school, he debated and played varsity soccer.

“I trained, practiced several hours a day, played in competitions and applied to and was accepted into Oberlin Conservatory for piano performance,” he explained.

And yet a concurrent fervor was brewing for his second artistic outlet, dance.

“I have memories,” Creel, both wistful and joyful, said, “of jitter-dancing around the tile floors in my kitchen, just not really knowing what to do but flailing around whenever music came on — because it was impossible not to.”

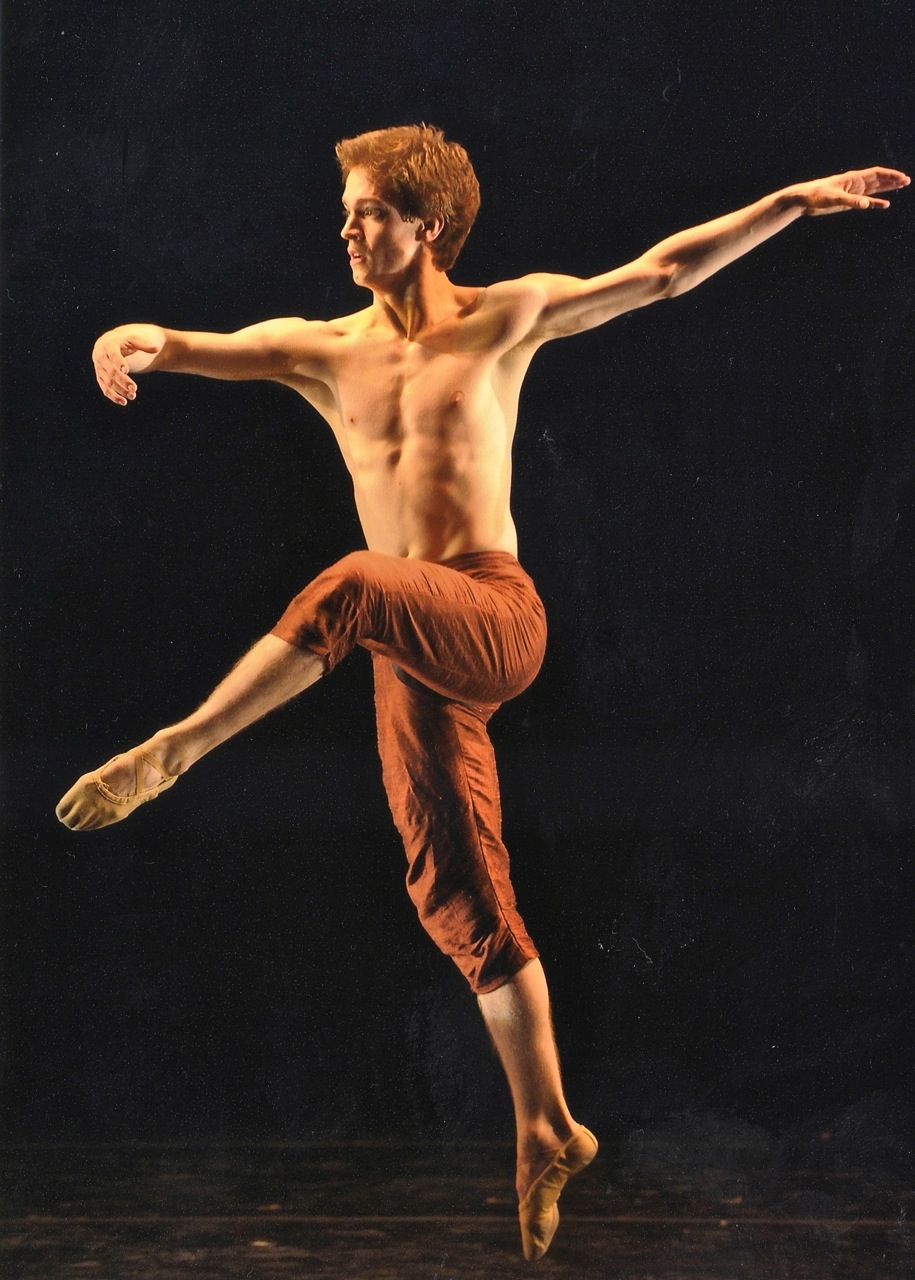

The draw of dance quickly grew on him, fueled by summers of what he calls “ballet bootcamps” and a gap year spent training with the Boston Ballet. It was during that gap year he met Professor Rodger Blum, the director of the Dance department at Smith College.

“He was this skinny, alert, hyper kid with way too much energy,” Professor Blum reminisced to me. “He just wanted everything right away, it just had to happen.”

Creel’s “everything” didn’t just include piano and dance. From a very young age, his family instilled in him a love for poetry: “We had this tradition…we called them ‘poetry bashes.’ We’d sit around the living room with piles of poetry books around us and go around in circles reading poetry.” And so choosing a school was not merely a matter of deciding where he would receive the best artistic training — Creel was determined to receive a liberal arts education while training to become a professional-class artist. After touring the Five College dance department and Amherst itself, he decided that it was the place for him to do so.

Excelling Academically

From his first-year seminar — Friendship, taught by Professor of English Kim Townsend — Creel distinguished himself as an outstanding student. After taking a seminar with Professor Townsend the next spring, Creel joined a reading group with the professor and a few other students that continued to meet throughout his time at Amherst. Professor Townsend also recommended Creel to Professor Sofield for a poetry seminar.

“He said, ‘I’ve got this magnificent student,’” Professor Sofield told me of Professor Townsend’s correspondence, “‘maybe the most interesting student I’ve ever taught’ — and Kim has taught here for more than 50 years.”

After receiving Professor Townsend’s laudatory email, Professor Sofield took Creel, then a sophomore, on as a student in a class on lyric poetry that Professor Sofield co-taught with Richard Wilbur. In class, Creel proved to be a deft critic of poetry, writing a 25-page paper on Wilbur himself and his then-recent publication, “Anterooms,” that Professor Sofield described as “superb.”

Open Ears, Open Heart

But outside the classroom, Creel demonstrated his interest in erudition through conversation.

“I’ve had a lot of conversations with Roger about matters academic,” Professor Sofield said, “But not just academic, because he’s such an accomplished person in various ways — and he’s a wonderful, wonderful conversationalist. He’s a wonderful talker, he’s a wonderful friend.”

If there’s one thing Professor Sofield, Richard Wilbur, geology professor Tekla Harms, Professor Blum and Matt DeButts ’14 have in common, it’s that they all have enjoyed and noticed Creel’s superhuman (and yet, inherently human) ability to connect with others.

Professor Blum: “I think I’m going to have withdrawal [when he graduates] because he…he really listens.”

DeButts: “When you’re talking with him, you don’t feel like he has anywhere else to be.”

The driving force behind his abilities a listener seems to be his endless curiosity.

“I’m interested in the minds that are around me,” Creel said. “I like the questions they ask, the questions I hadn’t thought to ask, the questions they suggest.”

Always looking for something to learn, Creel is eager to engage others about anything — relationships, poetry, dance, 18th century novels of the sea. He told me with his characteristic smile, “It’s all exciting. And Amherst professors have spent their lives trying to get people excited. It seems like a waste not to respond.”

Rocking His Major

This curiosity is what led Creel to Geology late in his Amherst career. His introductory Geology instructor, Professor Harms, knew he had been hooked after she noticed “learning one new thing about Geology would make him want to know the next thing and ask the right question, the kind of attentive question that shows he’s thinking about the next step.”

Creel noticed it too: “I found geology and thought, ‘My gosh, I come out of every Intro Geo lecture trying to grab people and teach them what I just learned. Give me more of this!’” He quickly became a rising star in the department, so much so that the Geology and English departments nearly came to blows while vying for a thesis from him. It was with much delight that Professor Harms noted the victor of that battle, and not just out of sheer departmental pride — Creel went on to write a thesis that earned him summa and the top thesis prize in Geology. She truly believes that Creel “has a contribution to make to the field.”

Tough Decisions

And so, Geology was added to Creel’s already-hard-to-keep-track-of litany of interests. Even though his determination seemed endless, this expansion meant that he had to leave behind some aspirations. No longer would he pursue a major in Biology. And as Creel became more involved in the dance world, performing in pieces by Mark Morris and Merce Cunningham, he made the difficult decision to give up rigorous piano training.

“I know that was a really hard choice for him,” Professor Blum told me.

Creel, recalling difficult periods of his time at college, said, “All I can hope is that we all trust that each of us does what we ought to do most of the time. Or at least attempts it.”

A True Liberal Arts Student

Thus, while he trimmed back on his commitments, he also deepened his passion and knowledge about each of his individual areas of interest, as he put it himself, “curious meandering along the edges of limits.” As a student of multiple fields — as Professor Harms described him, a “polymath” — Creel can’t help but “take the lessons that I learn from each and bring them back into the core.”

While he finds that his interests often connect — “Dance touches the instantaneous moment of present existence, and geology touches the farthest expanse of time that you cannot comprehend” — he must, as always, be aware of the different worlds he enters when practicing in each field.

“It’s an honest existence in each of the spheres,” he said, “not somewhere in a compromising center.”

And yet, his creative expressions are delightfully interdisciplinary. He danced the lead role in Professor Blum’s ballet based on the life and works of Leonardo da Vinci; Creel also performed and co-choreographed, with Amherst dance Professor Paul Matteson, a piece based on the lectures of renowned geologist Edward Hitchcock, Jr., a performance I was lucky enough to attend myself. It was a refined work of physicality, taking its spirit from the amusingly lapidary words of Hitchcock directly: “The ability to romp in a manly way ought to be encouraged; it keeps the soul young and elastic.” It was as if Creel, who received a Pease Fellowship to utilize the archives in generating a creative work and had thus only encountered these lectures very recently, had been on the same page as Hitchcock his whole life.

Creel’s effervescence and the scope of his accomplishments are hard to capture in such a short piece. I don’t have time to write about the frolic he and Professor Blum shared in the streets of New York City in the rain, all the while discussing geology, or how Creel managed to get a ticket to the final performance of a renowned modern dance company, armed with only his charisma and dedication, or about washing the walls of Charles Pratt with DeButts, or how he would listen to his mother recite epic poetry over the phone for hours at a time.

But, I suppose, that’s the legacy that Creel leaves — the stories, the lessons, the relationships of the years that have passed. As he goes on to perform with the Louisville Ballet next fall, he will continue to explore his limits, possibly going on to pursue a Ph.D. in geology in the distant future. If his success thus far is any indication of what his future has in store, Professor Harms will be right: “I think he’s one of those people who might be able to have it all.”