“Salinger,” a documentary directed by Shane Salerno, hit theaters Sept. 6, a release date that was chosen so the film would qualify as candidate for the 86th Academy Awards. Unfortunately, Salerno did not take into account any other qualities of Oscar-winning films in the making of this documentary. With a score that will rattle your bones and have you questioning whether you entered the correct theater (perhaps you accidentally wandered into “Insidious: Chapter 2” instead?), “Salinger” is 120 minutes of pure sensationalism and phoniness that Holden Caulfield would shudder to behold. The film’s main draw, and the focal point of its advertising campaign, was the promise of major revelations regarding the future release of Salinger manuscripts that have long been kept under wraps. “Salinger” delivers on this promise by revealing, in overly dramatic fashion (true to the outrageously overwrought nature of the film), the fact that there are plans for more Salinger novels to be published as early as 2015. We’ll see.

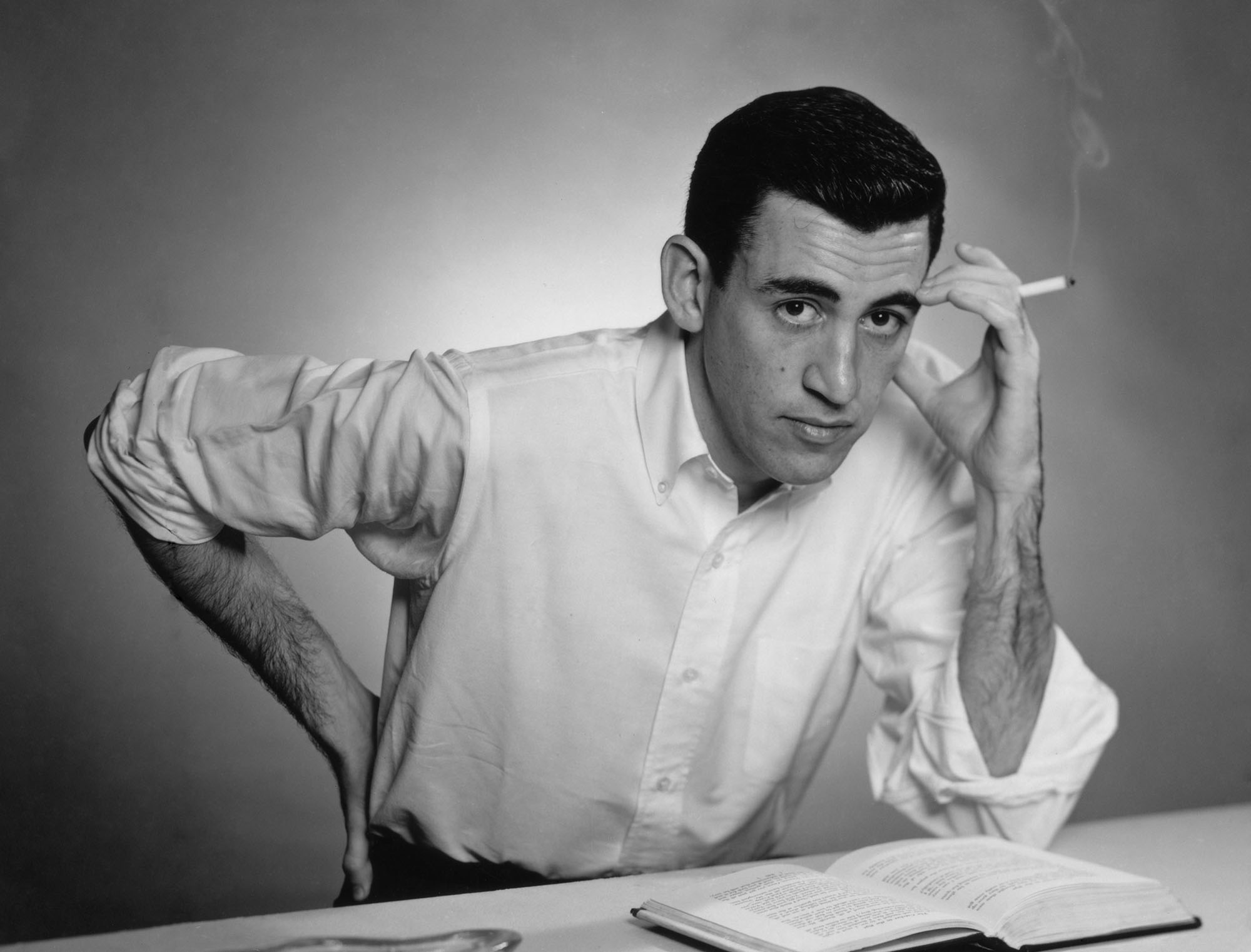

The film mainly features talking-head interviews with old acquaintances, friends, family members, lovers and fans of Salinger. These interviews are supplemented by footage of embarrassingly obvious reenactments of Salinger sitting at a typewriter or wandering through the woods towards his infamous, isolated “bunker” — footage that is more often than not (unintentionally) laugh-out-loud funny. Images selected from a rotating cast of four or five black-and-white stock photos of Salinger, in which he is seated at a typewriter and his facial expressions vary from frowns to wide grins, are displayed on the screen as an accompaniment to anecdotes that describe Salinger as being happy, sad or melancholy/in deep thought.

Almost all of the interviews completely blow out of proportion both Salinger’s writing and Salinger as a person, making aggrandized claims about the nature of his writing as well as America’s reception of his writing, which are always unnecessary. The interviewees agree that Salinger’s writing changed the fabric of American society, and possibly even the world as they knew it, with one fan even expressing his initial reluctance to read “The Catcher in the Rye” because he didn’t want his life to be changed. Fans and family members alike decide that Salinger’s reclusiveness was actually a call for attention — he wanted to be thought and talked about. They, in turn, seek him out with an avidness that edges towards full-blown stalking. The film opens with an ex-Newsweek photographer reenacting and narrating his 1979 stakeout of Salinger at the local post office in Cornish, N.H., taking great pride in his successful violation of the privacy of a man who so clearly valued it. Later in the film, a passionate fanatic of Salinger’s recounts the day, so many years ago, that he drove 400+ miles to Salinger’s home in the mountains of N.H. to wait at the end of Salinger’s driveway until Salinger emerged.

Another aspect of Salinger’s life that the film overindulges in, to the point of yet more sensationalism, is his time as a soldier during World War II. Salinger took part in more than 200 days of combat, after which he worked with the Army Counterintelligence Corps in Europe in order to help seek out members of the Nazi Party and bring them to justice. Gratuitous images of piles of corpses with their flesh burned off are constantly shown throughout the coverage of Salinger’s time in the war. The fact that Salinger worked on “The Catcher in the Rye” during his time as a soldier and carried pages of it with him while in combat is wildly overemphasized, forcing the point that Catcher may have its roots in the theme of war down the audience’s throats again and again.

The majority of the interviewees express a feeling of entitlement that they seem to think goes hand-in-hand with their appreciation of Salinger’s work: because they treasure his art so thoroughly, they have a right to violate his privacy, which they ultimately succeed in doing in contributing to this film. Repetitive, indulgent interviews with Salinger’s much younger ex-love interests — among them, Jean Miller, who was about 15 years younger than Salinger, and who is said to have provided the inspiration for his story “For Esmé – With Love and Squalor,” and Joyce Maynard, who lived with Salinger in the 1970s — are dwelled upon in a cringe-inducing manner. They expose details of Salinger’s romantic behavior that, although truly worrisome, are obviously included in the documentary purely for the entertainment value and come off as more intrusive and seedily presented than anything else. Although almost everyone who appears in the film constantly sings Salinger’s praises to an eye-rolling degree, they simultaneously undermine him by exposing and ruminating upon every bit of his private life they can get their paws on.

The entire film smells of betrayal and undoubtedly has Salinger rolling in his grave. “If there’s one thing I hate,” says Holden Caulfield in the beginning of “The Catcher in the Rye”, “it’s the movies. Don’t even mention them to me.”