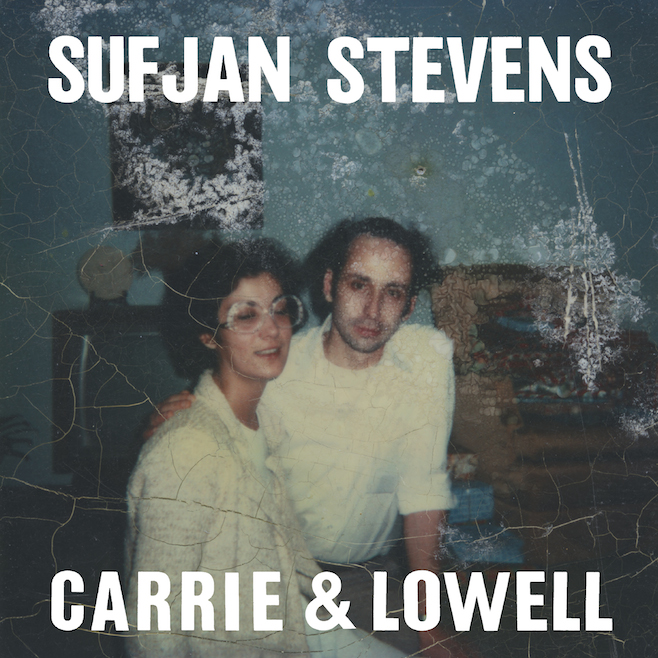

“And I don’t know where to begin,” Sufjan Stevens sings in the first verse of “Carrie & Lowell,” his seventh studio album. He has taken on quite a daunting task: to honor the few remaining memories he has of his mother Carrie. She left the family when he was just one year old, but Stevens still spent three summers with her in Oregon, between the ages of 5 and 8. Now that she has passed away in a hospital bed, those summers’ stories are all he has. But what can you do with sparse memories like that? What form do they take on when they’re all that’s left of your mother? How do they haunt you?

There is a spectral quality to this whole album. I mean that in all senses of the word — both as in being about ghosts and apparitions and having a ghostly or unreal, ephemeral quality to it.

“There’s only a shadow of me; in a manner of speaking I’m dead,” Sufjan sings on “John My Beloved.” He imagines his mother as a ghost too; her “apparition passes through [him] in the willows,” in “Death With Dignity.” During an intimate interview with Ryan Dombal from Pitchfork, Stevens even recalls feeling “possessed by” his mother’s “spirit,” “predisposed to her pattern of destruction.” Many of Stevens’ lines are fleeting visions of the past, and visual metaphors are abundant. This, too, has to do with specters; the word comes from specere, Latin for “to see.” And the metaphors and visions blur to the point of being indistinguishable. Stevens conjures up spectral scenes for us in, for example, “Death With Dignity.” There’s an “amethyst and flower on the table” and a “silhouette of the cedar.” But Stevens asks us and himself: “Is it real or a fable?” Other visions flit by, unexpectedly and unexplained, and start haunting the songs they’re part of. Again, here’s “Death With Dignity”: “Your apparition passes through me in the willows/ Five red hens — you’ll never see us again.” What do the five red hens do here? I can imagine they strutted around Carrie’s Oregon house. Stevens somehow connects the hens with the sensation of his mother’s apparition and makes an associative leap, but I don’t think any transcendent meaning emerges for either us or Stevens.

The way he forges those haiku-like lines out of his memories reminded me of “In a Station of the Metro” by Ezra Pound, a poem of one sentence in two lines that goes like this: “The apparition of these faces in the crowd;/ Petals on a wet, black bough.” Scholars have extracted all kinds of complicated meanings from the poem, but Pound’s own words capture the poem’s meaning best. In “Vorticism,” he writes, "In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective." That seems similar to how we can make sense of Stevens’ mysterious anecdotes from his summers in Oregon. For him, recording them is valuable in itself, as a way to honor his mother.

I also need to talk about the music itself. Let me first say that musically, this album feels totally unlike his earlier work. It’s cut down to a quivering core. It’s close to the bone. Thus it gets close to your bones and cuts down to your core, too. What’s so spectral about it? On most songs multiple voice tracks are superimposed with a slight delay between the layers, giving Stevens’ singing an uncanny vibe. Most songs end with surprising but beautiful ambient or post-rock style walls of sound, reproduced to a devastating effect in his live performances. “Blue Bucket of Gold” and “Fourth of July” are driven by a distant piano that pulses like not-quite a heartbeat. In the background we sometimes hear a sea or an Oregon brook. Most songs are accompanied by acoustic guitars that sing with Sufjan’s fingerstyle touch. They sound “bright as the Oregon breeze,” but become haunting and eerie when combined with his dark “prose poem of depression,” as Stevens described this album to Pitchfork.

Then there’s the question of the therapeutic value of this record, which might turn out to work against its artistic value. Indeed, the mystifying moments of poetic juxtapositions have the most artistic value for me, but might not be therapeutic; there’s no easily accessible, comforting meaning. They seem at odds with and are outnumbered by all those instances in which Stevens mythologizes Carrie’s legacy to the point of trying to exorcise the parts of her that possess him, thus creating a comforting narrative.

“I’m prone to making my life, my family, and the world around me complicit in my cosmic fable, and often it’s not fair to manipulate the hard facts of life into a vision quest,” Stevens told Pitchfork. “It’s all an attempt to extract meaning, and ultimately that’s what I’m in pursuit of, like: What’s the significance of these experiences?” Some examples: “Signs and wonders: Perseus aligned with the skull/ Slain Medusa, Pegasus alight from us all,” from “The Only Thing” and, “Carrie surprised me/ Erebus on my back / My lucky charm,” from “Carrie & Lowell.”

Stevens’ language is telling: He is in pursuit of meaning, on a quest, fueled by the desire to be with his mother. When Carrie’s ghost starts haunting him, it may seem like she’s with him, but is that really what he wants? She becomes a ghost after all. And she’s everywhere, all the time, which is too much for Stevens and his senses: In “The Only Thing,” he asks Carrie, “Should I tear my eyes out now, before I see too much?” The world is too much with him, a result of the violence and restlessness of his metaphors. They stop both Carrie and Sufjan from resting in peace. And as a result, this constant search for meaning sometimes feels exhausting. Stevens’ desire for meaning turns pathological: He feels either too much or too little — in “I Should Have Known Better” he simultaneously feels “that empty feeling” and is frightened and deceived by his feelings.

There’s a way in which Stevens does seem to have an answer to the question of how to honor the memory of his mother, both the good and bad, the absences and presences, without eulogizing her to the point of pretension or deceit. “When I was three, three maybe four / She left us at that video store/ Be my rest, be my fantasy,” Stevens sings in “I Should Have Known Better.” Maybe a pregnant, restful fantasy is all he needs the memories of his mother to be. He should not “back down” but “concentrate on seeing/ The breakers in the bar, the neighbor’s greeting.” He continues: “My brother had a daughter/ The beauty that she brings, illumination.” And so Carrie’s legacy lingers in her beauty, and the beauty of this album, perhaps redeemed from the curse that currently haunts the Stevens family.